College Board’s avoidance of subgroup performance differences.

In the report “How the New SAT has Disadvantaged Female Testers,” I look at the impact the new SAT has had on its largest subgroup. That full report is not a quick read. It examines the changes on the new SAT piece by piece and looks at the interplay of those components. It’s meant to be as comprehensive as the current data allow. It seemed to demand a companion piece that was less sober and was willing to enumerate the mistakes and evasions College Board has made in this area. It is not meant as a Cliffs Notes for the in-depth report—which I would be delighted for you to read. It does explain, though, why the full report needed to be written—because College Board seemed to have no interest in doing so.

The research shows that high-performing female test-takers, in particular, were disadvantaged by the new SAT in comparison to the old SAT. This statement is quite intentional in its phrasing. No matter what one thought of the old SAT’s starting point—pro or con—the proportion of female students in top scoring ranges has declined. Moreover, this result could not have been a surprise to those developing the new exam.

College Board should state the policy it took on subgroup score differences in designing the new SAT.

College Board either violated the policy it once held of ensuring that subgroup “gaps that exist on the current test do not widen,” or it chose to abandon that policy. It is quick to use the shibboleths of “opportunity” and “equity” but slow to provide the research to back up those generalities.

College Board should share the data it had both before, during, and after the creation of the new SAT.

College Board has not gone on record with its findings on the shift in gender inequities on the new SAT and has remained similarly mum—beyond misleading press releases—on how observed results have changed among other subgroups.

College Board should explain why it stopped publishing key information.

College Board removed almost all data on gender and income from its annual report on college-bound seniors. It has not published—or at least not made them available on its website—supplemental data tables that are crucial to understanding SAT performance such as percentile tables by gender, race, and ethnicity. It last published those tables in 2015 and has now removed them from its site. Compass has reconstructed the data in order to show the change from old SAT to new.

The further disadvantaging of female students was a foreseeable consequence of the new SAT’s change in structure and scoring.

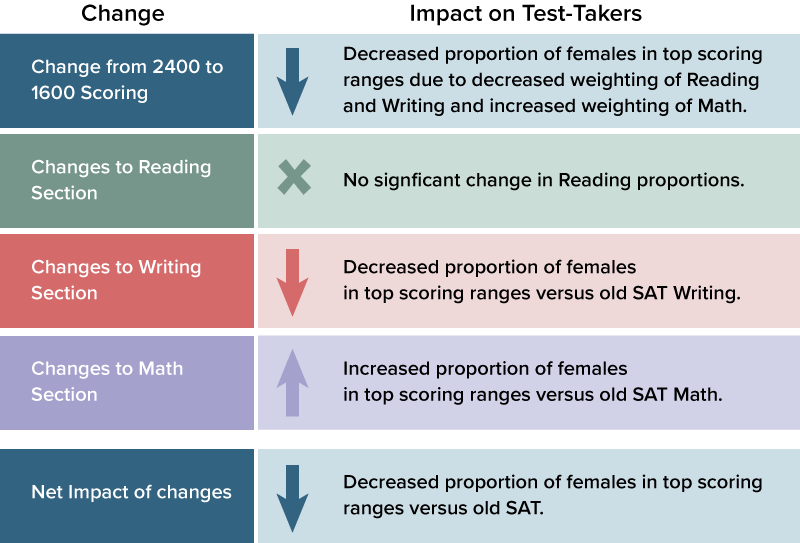

What was treated by David Coleman, president of College Board, as an applause line in 2014—the return of the prodigal 1600!—would not be viewed as enthusiastically by the thousands of female students now left out of the top score ranges because of the exam’s reconfiguration. How the various components contributed to the impact on female test-takers is summarized in the chart below. The full report provides the data and context.

College Board (and ACT) should commit to providing more information—at all score levels—of subgroup differences.

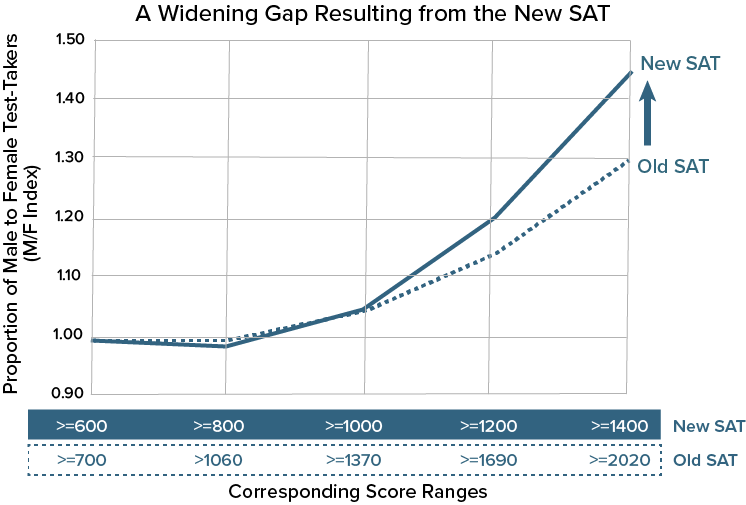

Mean score differences understate the impact on female students. Gaps that existed on the old SAT at higher score ranges have widened further. This widening occurred on an exam that was supposed to better align with the “the work students do in school.” Yet it is precisely such schoolwork where females outperform males. Why the additional disparity?

The difference in observed results for male and female testers must not be accepted as an inevitable result of standardized testing. It is not.

The SAT continues to lag ACT when comparing standardized mean differences of males and females. In fact, ACT scores for the class of 2017 showed females outperforming males at the mean, at least. There are still many concerns about the ACT as one moves away from the mean, but College Board should do more to address its own test’s disparity—even if only to dispute the claim.

The SAT and PSAT are increasingly government funded, and decisions regarding them are a matter of public policy.

For the class of 2018, approximately 1 million students will have their SATs paid for by state or local governments, and millions more will receive subsidized PSATs. Has College Board been upfront with those entities on the impact the new SAT has had on female students?

The invisible inequity of minimum scores, thresholds, and “cut scores.”

The SAT is not used solely for admission purposes. “Cut scores” at some colleges can determine merit aid and eligibility for honors colleges. The new SAT almost certainly exacerbated—without debate or publicly available research—female underrepresentation in these areas.

The mission creep of the SAT and PSAT has extended the import of score result differences into new terrain.

A popular justification for the PSAT is its use in predicting AP performance. College Board publishes “expectancy tables” by cut score and offers its judgment—on PSAT reports—of a student’s likelihood of success in 21 different AP courses. College Board is cautious in its phrasing of how this information is to be used, but the euphemisms of “Has Potential” and “Not Yet Demonstrating Potential” should not mask the PSAT’s own potential for gender-based steering. College Board has not addressed how the PSAT 10 and PSAT 8/9 may suffer from some of the same subgroup differences shown on the new SAT.

The research on score gaps should not inform individual student decisions.

Female students should no more ignore the SAT as an option as they should ignore STEM careers because of underrepresentation in those fields. Differences in population-level scores are not a verdict on individual performance. A student should try to identify the admission test that best displays her strengths.

Compass’ own research on this topic should be unnecessary, because it is properly the College Board’s responsibility.

College Board was afforded an immense amount of trust by having an entirely new test immediately accepted by every college in the country. It should repay that trust with a proper accounting of how the test performs. College Board has devalued internal research on the SAT and hobbled external research.

A concern is that the increasingly winner-take-all stakes in state-funded testing has made College Board more circumspect about attacking hard problems—and remediating subgroup differences is among the hardest—lest it provide an opening for the ACT. There seems to be an increasing trend toward a tightly controlled narrative and less expansive research.

My hope is that this piece and the full report are widely shared and, perhaps, provoke a response. Even an evisceration of my logic would mean that the College Board is paying attention to the issue and to its responsibility in addressing subgroup performance.