The Complete FAQ to What Happened, What Can Be Learned, and Who to Believe

The principals of Compass have been tutoring students for the SAT and ACT since the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, and none of us has seen anything remotely like what happened on the June SAT Reasoning administration. To cover the rather remarkable situation and its aftermath, we have prepared several posts that answer what happened, what was done right, what was done wrong, what the numbers really say, and what students can learn from the situation.

In addition to the FAQ below, you may also want to see:

4 Mistakes the College Board Made Regarding the June SAT

6 Things Students Can do to Prepare for Testing Mishaps

Q: What happened with the June SAT?

The SAT Reasoning test is administered in 10 sections: 1 Essay, 3 Critical Reading, 3 Math, 2 Writing, and 1 Experimental or Variable section (this can be any of the 3 subjects and is not part of the student’s score). The 8th and 9th sections of the SAT are always the 20-minute Math and Reading sections. About half of students receive Reading and then Math and the rest receive Math and then Reading. A printing error in the student booklets for the 20-minute Reading section stated that the section was 25 minutes long. The instructions read by the proctors, on the other hand, stated the correct length. The disparity caused all manner of confusion. Some proctors were immediately alerted to the problem, notified their students, and made sure that the section was correctly timed. Other students were not warned of the error by the proctors and assumed that they had 25 minutes. “Read the Instructions” is what we have always been taught. It is likely that some proctors allowed students to take 25 minutes. What is certain is that students took the section under differing and confusing circumstances, so the results of those sections could be called into question.

You can see the official College Board response here.

Q: If the printing problem was only on the Critical Reading, why was the 20-minute Math section also thrown out?

Some students were taking Math at the same time that others were taking Critical Reading. The confusion around timing thus impacted all students.

Q: How did the College Board justify the decision to consider the shorter test as valid?

College Board and ETS examined the data from a sample of student answers and, according to them, found that the data from the unaffected 25-minute sections were sufficient to accurately score students’ tests. It was decided that the 20-minute sections would be un-scored. We examine that decision in more depth. The short answer is that it was a relatively fair and sensible solution to a horrendous problem.

Q: How is ETS involved? I thought the College Board gives the SAT.

The relationship between College Board and Educational Testing Service is one of the longest and most lucrative in testing. Although College Board owns and promotes the SAT, it is highly dependent on ETS for much of the heavy lifting in developing and analyzing tests and for all of the test administration and security. In the movies, when a testing bad guy is needed, he comes from ETS (Stand and Deliver). When high school students dream of stealing the SAT, it is from ETS headquarters in Princeton (The Perfect Score). When Ralph Nader wrote his screed against testing, Reign of Error, it was about ETS. David Owen’s influential and irreverent None of the Above? ETS. As much as a third of College Board revenues go directly to ETS, which is also deeply involved in the Advanced Placement program. I will sometimes use “College Board” to stand for both organizations, because they are so intertwined on the SAT.

Q: Why didn’t the College Board invalidate all scores?

Because a better alternative existed, and, cynically, because the bad thing happened to too many students to sweep it under the rug. Problems occur regularly because of fire alarms, test interruptions, proctoring gaffes, and other security breaches. What made this event different was its almost unprecedented scale. Individual problems have sometimes gone uncounted — rarely, though — but, to my knowledge, entire sections have never been eliminated. When an incident occurs within a test center or at a handful of test centers, ETS will typically investigate and invalidate scores and invite students to take the test again for free. In some cases, a special administration is arranged within a week or two. Needless to say, this solution is never popular with the students it impacts. Nor would a special administration have been possible for the hundreds of thousands of students who took the test in June. The idea of invalidating nearly one-half million exams provided a lot of motivation to come up with a different solution. Some have questioned whether there might have been too much motivation.

Q: Doesn’t this mess up the scale?

Yes and no. By using the Experimental section of every exam, College Board can equate one form of the test to another and that to another and that to another, so that scores on one form are equivalent. The experimental section was correctly administered, so the data could be used to place the June results on the same scale as May or January or November scores. There are at least two problems, however. The first one is a statistical issue that ETS calls the Equal Reliability Requirement. We will defer the mathematics but will state that it is unclear whether this requirement was violated. The second problem is a little easier to explain — only a little. The standard Math SAT has 54 items, so a student can get anywhere from 0 right to 54 right (we are ignoring the “guessing penalty,” because it adds nothing to the discussion). There are 61 scaled scores than can be assigned from 200 to 800, counting by 10s. There is never perfect one-to-one mapping between raw scores and scaled scores and the scales differ slightly from form to form to account for small differences in item difficulty. But at least you have enough items to come close to an ideal mapping. On the June test, the most scored Math questions that a student could have answered correctly was 38. There are still 61 scaling slots, so there are going to be more gaps — some scaled scores will simply not be achievable. This also makes every question worth a bit more than it normally would be. The scale is likely to follow the usual curve, though, and overall student scores will be in line with scores that would have been received on the full test. Dropping hundreds of thousands of results would not have changed the scaling for future tests, but it could have dramatically altered the test taking pattern of students and created a blip on longitudinal data.

Q: Does this mean June was harder? Easier?

Neither. Missing an extra question in June might drop your Math score from 620 to 600, whereas in May it might have dropped from 620 to 610. But the reverse is true, as well. You could have gained 20 points by answering one more question correctly. [These numbers are made up. We won’t have scores for another 2 weeks.]

Q: Would my scores have been different with the 20-minute section?

This one is impossible to answer. What we can strongly surmise is that about as many students would have scored higher as scored lower. But the way the SAT is constructed, few scores would have been impacted by more than 10-20 points. If you correctly answered 70 percent of the problems in the first two Math sections, it’s unlikely that you would fall out of the range of 60-80 percent of the problems on the last section. There is nothing special in those problems that make them different from all other problems. The truth lies somewhere between College Board’s “nothing to see here” response and some of the more breathless reactions in the media. It’s simply not true that the loss of the 20-minute section suddenly made it impossible to differentiate a 700 scorer from an 800 scorer. One problem is that the SAT has long been thought of as having a greater degree of accuracy than it actually provides. The SEM or standard error of measurement is a way of expressing how close a test can approach a student’s “true score” — the one they would receive if they tested repeatedly on parallel forms. Both Math and Reading have SEM’s of about 30 points. This means that a student scoring 550 has an approximately two-thirds chance of scoring between 520 and 580. Expressed another way, the student has a one-third chance of having a true score outside of that range. Far too much is made of 10-20 point differences. Neither the SAT nor the ACT can claim that level of consistency.

Q: Will I find out how I did on the un-scored sections?

College Board has not specifically addressed this, but past incidents of invalidated problems strongly indicate that they will not release results from those sections — it would fan the controversy again without providing a fair solution for all students.

Q: I didn’t take the test in June, but I took in in May. Will the June results impact me?

No. June testers, as a group, will receive no benefit or penalty over other testers. One reason that College Board wiped away the 20-minute sections was to ensure that overall scores were not biased. You may see more of your friends taking a free test in October, but you are otherwise not impacted.

Q: So why the fuss?

You don’t throw away almost 30% of a test and not suffer some statistical consequences. Test makers refer to reliability which, in short, is how likely a student is to earn similar scores on differing test forms. All things being equal, making a test longer will add to its reliability. But as a test gets longer, each additional question adds less and less to that reliability. What College Board is saying — although they refuse to state it so bluntly — is not that the loss of 30% of the test has no impact, but that it has an acceptable impact. According to College Board: “[we] will still be able to provide reliable scores for all students.”

No test is perfectly reliable, and even the full-length tests that ACT and SAT administer vary in reliability throughout the year.

Q: Why does test length matter?

You can think of any test as a sampling of what you know or how strong your skills are. If I ask you five US history questions, I’ll get a rough sense of whether or not you are a history buff. Another 10 questions and I’ll start to get a sense of where your gaps are. Another 20 questions, and I’ll likely be able to place you against other people I’ve tested. Another 30-40 questions will let me do that accurately and consistently. But how much more am I going to learn by asking you yet another 5 to 10 questions that I haven’t already learned? College Board wants us to accept that they already asked enough questions.

Q: Are June scores valid?

College Board and ETS say they are valid and that they will report them to colleges. Colleges do not, as yet, have any reason to question the legitimacy of June scores, and I don’t expect anyone to announce asterisks or score boycotts.

Q: Seriously, was the test really long enough to be valid? [Scroll ahead if you don’t care to see lots of math.]

College Board and ETS are not providing their numbers, but we can do some calculations on our own based on what we know about the SAT. The non-math answer is that the test was probably long enough — although this circles back to the difference between acceptable and ideal.

Test reliability is something that test makers assiduously measure. It tells them how accurately they are making one form equivalent to another. It tells them how much student scores are likely to vary from a theoretical “true score.” It can help or harm the validity of scores — how accurately scores predict college GPA.

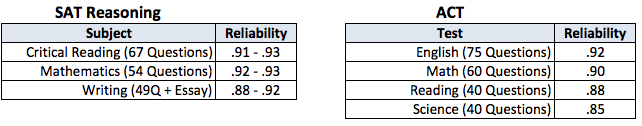

Below is a table of the reliability ranges, as reported by the College Board, for all test dates in 2013. As a point of comparison, I have also provided the reliability ratings for the ACT as reported in the ACT Technical Manual (this was a specific study, so it does not show ranges. In real life, ACT reliability varies from form to form just as SAT reliability does.).

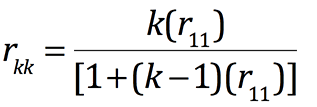

The figures for the SAT are considered quite good. Say what you will about Educational Testing Service, but they do know testing. In my history test example, I pointed out that there is a positive correlation between test length and reliability. So if the 20-minute sections were thrown out, what would happen to the reliability? Would College Board be able to as accurately predict your “true” score. There are any number of ways that psychometricians measure reliability versus test length, but one of the oldest is with the Spearman-Brown formula.

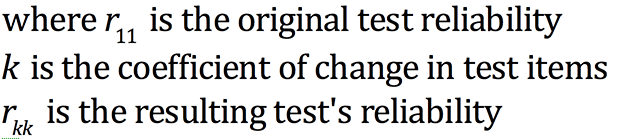

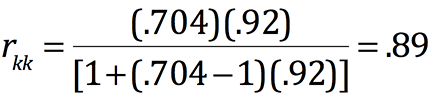

As test formulas go, this one is not bad to work with. We know that SAT Critical Reading and Math have reliabilities ranging from .91 to .94. For lack of a better value, we’ll take the median reliability for Math in 2013 and use that as the hypothetical validity of the full-length June test. The Spearman-Brown formula allows us to predict the reliability of a shortened exam. In the case of the June SAT, 16 of the 54 Math questions were thrown out (College Board insists on the more genteel “un-scored”), so the test was only 38/54 or .704 as long. That is our value for k.

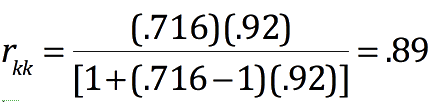

Doing the same thing for Critical Reading, we can say that 19 of 67 questions were omitted, so the test was 48/67 or .716 as long as it should have been.

Doing the same thing for Critical Reading, we can say that 19 of 67 questions were omitted, so the test was 48/67 or .716 as long as it should have been. The resulting predicted reliabilities of .89 fall outside of the usual range — that was almost guaranteed — but are they “good enough”? The table above shows that the Writing test had reliability as low as .88 in 2013 alone (a wider period of time would have more outliers). And the reliability for the ACT Reading and Science were reported as .88 and .85, respectively. In fact, we should not be that surprised at the comparison between the June Critical Reading and ACT Reading. Even the shortened SAT Critical Reading had 48 scored questions given over 50 minutes. The ACT Reading has only 40 questions in 35 minutes. The Science Test has the same length as the Reading Test.Going back further in the vault, we find that reliability scores of older SATs regularly fell into the .87 – .88 range. So the quick-and-dirty conclusion is that while the error-shortened SAT was not the best exam College Board has ever offered, it does, indeed, fall in the range of acceptable.

The resulting predicted reliabilities of .89 fall outside of the usual range — that was almost guaranteed — but are they “good enough”? The table above shows that the Writing test had reliability as low as .88 in 2013 alone (a wider period of time would have more outliers). And the reliability for the ACT Reading and Science were reported as .88 and .85, respectively. In fact, we should not be that surprised at the comparison between the June Critical Reading and ACT Reading. Even the shortened SAT Critical Reading had 48 scored questions given over 50 minutes. The ACT Reading has only 40 questions in 35 minutes. The Science Test has the same length as the Reading Test.Going back further in the vault, we find that reliability scores of older SATs regularly fell into the .87 – .88 range. So the quick-and-dirty conclusion is that while the error-shortened SAT was not the best exam College Board has ever offered, it does, indeed, fall in the range of acceptable.

Q: Does ETS have better ways of measuring reliability?

Yes, they do. Advanced methods exist in both classical test theory and item response theory. If ETS or College Board care to share the results of their analysis using those methods, I’d be more than happy to report them. ETS also has access to that super-secret experimental section that I mentioned earlier. It would be surprising to me if they did not use that additional section to gauge the impact of the missing 20-minute sections. No, the experimental would never become a part of a student’s official score, but it would have provided valuable information about how accurate the initial sections of Math and Critical Reading had been.

Q: What about that Equal Reliability Requirement?

To claim that two tests forms are equivalent is not something you can do simply because you think that they look alike. The tests must meet specific content and statistical goals. Tests with widely differing reliabilities cannot be equated (and equating is essential to both SAT and ACT). It’s generally up to the testing agency, though, as to how equal “equal reliability” really is. The test makers get to judge their own tests — although ETS and College Board do publish regular research.

Q: Should we sue?

Criticism is warranted, but it is not clear what damages would be collected via class action. Students went through at least two days of intense anguish, but, fortunately, they will still receive scores. I do believe that College Board should be more forthcoming about the data that led it to conclude that scores would still be reliable. Thanks to public shaming, College Board will provide June SAT students the opportunity to take the October SAT for free. Given the number of spring juniors who repeat the SAT in the fall, I would expect this to cost College Board, ETS, or their insurers millions of dollars. “[We] have waived the fee for the October SAT administration for students who let us know that their testing experience was negatively affected by the printing error and we will continue to do so.” Students wanting to retake in October should be sure to use the magic words — “negatively affected.”